Yesterday, we detailed what we know about the upcoming Tonari no Trans Shojo-chan, directed by Shôji Tsuyoshi, an award-winning bisexual director. Our readers, though, may be curious as to his other works: what are they like? What is his style of film-making?

So today, we’re going to take a look at his first feature-length film, Old Narcissus. A story about aging, generational gaps, family, and confronting limitations. Let’s gaze deeply into the pool that is Old Narcissus.

简介

Adapted from his short film of the same name, Old Narcissus follows Kaoru Yamazaki, a children’s book writer and illustrator in his 70s. When he was younger, he was the toast of the gay scene: self-assured, arrogant, but with the physique and the looks to back it up. The body was was tea, and the face card was never declined.

Eventually, however, time comes for us all. Now alone in old age, aside from some old friends in a bar, one evening he decides to hire a young man named Leo for the evening. He becomes smitten with the young boy and his good looks, and Leo in turn is impressed that he is the illustrator of a book he adored as a child.

As the two go on more paid dates, they become closer, and the differences and similarities between them become clear. As Yamazaki begins to question his life as an eternal bachelor, so does Leo begin to reconsider his reluctance to start a real family with his boyfriend. Together, the two experience the highs and lows of love and lust for gay men in modern Japan.

A New Tragedy for Narcissus

Famously, the mythological Narcissus, after staring into his reflection in a pond, was so captivated by his own beauty that he turned into the flower that bears his name in his passion — or, in some interpretations, drowned in the pond as he tried to find his “love.”

In this retelling, we start on an image of Yamazaki, old and naked, in a void but for the water beneath him, staring into his reflection, distraught. As someone who was not just a talented artist and writer as a youth, but intensely beautiful, he has grown to become frustrated and angry at his aging, lamenting the difficulties of growing old, and now suffers from writers’ block — a problem when the 50th anniversary of his best-selling debut book is coming up, and he has been asked to create something new.

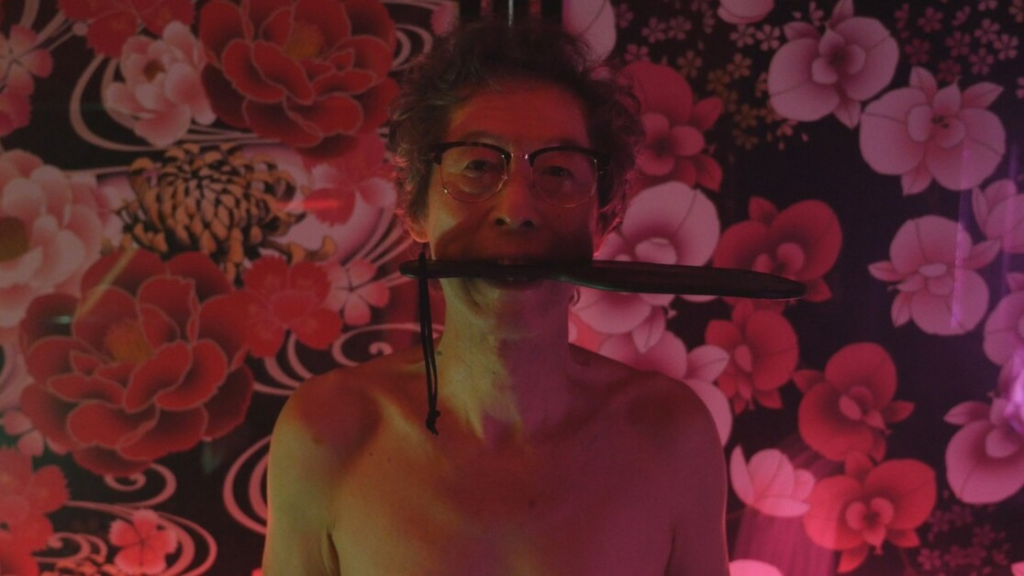

However, now, he finds that even his old pleasures do nothing for him. In an early scene, he pays Leo to punish him with a leather paddle, which was a source of joy for him as a younger man, as he imagined (or, using a mirror, would see) the high aesthetics of an incredibly handsome young man as the center of attention, which sublimated his pain into pleasure. But when his dom is much younger and more beautiful than him, his pain is just… pain.

However, there are some things that still remain. His abusive father forced him to play baseball when he was a boy, but this skill remains, and he easily outdoes Leo when they visit a batting cage on a date. Additionally, Leo tells Yamazaki, when he is at a low point, that “your books have saved lots of kids like me,” and the book remains popular to this day, so some part of him will be forever young.

The tragedy for Yamazaki is not that he is entranced by his own beauty, but that now when he looks at his reflection or thinks about himself, he is ashamed and upset by the now old man who looks back at him. Through his relationship with Leo, however, he begins, albeit slowly, to think about — and to love — somebody other than himself, and so saving him from drowning.

Divisions and Unities

The contrast between beauty/youth and age/faded looks is not the only divide that the film explores. One of the biggest differences that is explored is that of generational attitudes, not just aesthetics. Early in the film, Yamazaki, still arrogant, insults a homeless man collecting cardboard and cans, while Leo is kind towards him. Indeed, Leo is kind to everyone he meets, while Yamazaki retains the selfishness and bad attitude of his youth. There is, perhaps, a reason for this, though.

At one point, the two visit the grave of one of Yamazaki’s old friends, who passed away from complications of HIV/AIDS, Yamazaki muses that he has no family and cannot have children, and that he thinks it is ironic that he is a children’s illustrator. Leo replies, “They wouldn’t think that overseas. Japan will catch up.” But Yamazaki replies, “That is there, and this is here.”

The difference in views between someone who grew up in an age where even the word “gay” was new to Japan (even if the experience was not) and someone who has grown up in an age where, while full equality is not realized, is optimistic that the necessary changes will come, highlights the differences in the general atmosphere of life as a gay man that has taken place in just half a century. Yamazaki’s coldness is not just the result of his vanity, but also a reflection of the world he grew up in — as is Leo’s kindness.

We also see a divide in the interpretation of family, and what it means. Hayato, Leo’s boyfriend, has a supportive and understanding family, who were excited and happy to meet Leo. As such, Hayato is trying to encourage Leo to join with him in a Partnership Oath, to make their relationship official.

Leo, however, who grew up without a father, and at odds with his mother, is hesitant to join a family. Yamazaki concurs with this view, believing that having a family is troublesome. However, Yamazaki thinks this because his father was abusive, while Leo is jealous that Yamazaki had a father at all.

This is also reflected in the difference between the way that Hayato and Yamazaki try to induct Leo into their family: Hayato wants Leo to join using the Partnership Oath, as mentioned above, while Yamazaki asks him to make their relationship official by adopting him, a method which is considered somewhat outdated today, but which for many people was (and in some cases, still is) the only way to guarantee rights. Without marriage equality, these kinds of issues will continue into the future in Japan.

结论

Old Narcissus is an excellent film that is well worth a watch. Emotionally rich, well acted, and a perfect set of the contrasts and similarities between generations and beliefs, the film reveals that, in the end, beauty is not dependent on youth, and wisdom is not dependent on age.