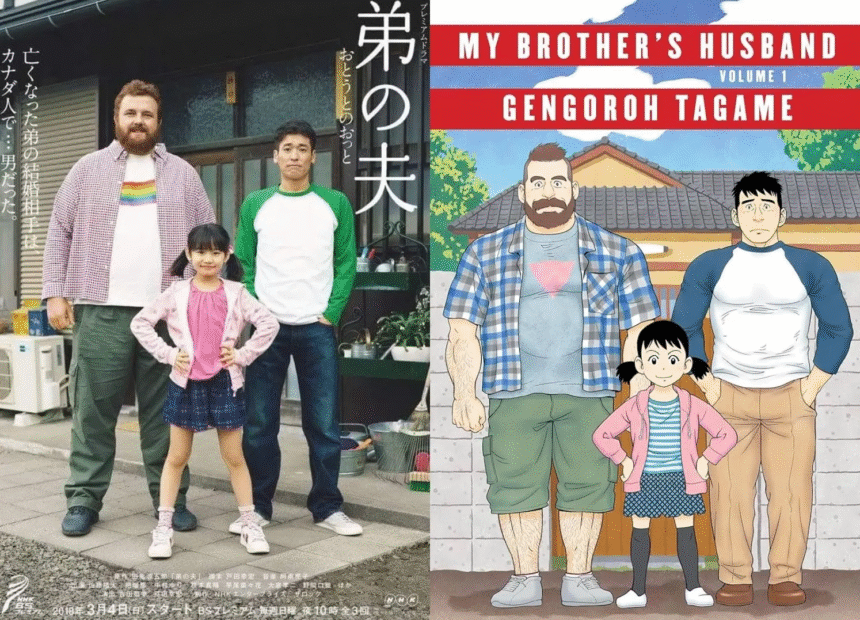

2018 年,NHK 制作了三集电视剧《我哥哥的丈夫》,该剧改编自画师田龟源五郎 2014 年创作的同名漫画。该剧日文名为《Otouto no Otto》,讲述了被接纳的困难、克服偏见以及成长可以来自任何地方、发生在任何人身上的故事。

Tagame 的漫画以其 BDSM 艺术作品而闻名,其深思熟虑、细腻的故事和标志性的出色艺术作品获得了好评。那么,真人版的改编效果如何呢?

情节概述

故事以倒叙的方式开始,年轻的折口八一向弟弟亮司夸耀自己有了女朋友,并说亮司一定在吃醋。亮司告诉孪生弟弟自己是同性恋并逃跑后,年长的亮司从梦中醒来。他一直梦见自己的哥哥,因为今天有客人要来:迈克-弗拉纳根。

迈克是亮司的丈夫,但亮司在故事开始前不久去世了,他去加拿大留学后再也没有回来。迈克拜访八一,不仅是为了第一次见到八一的大家庭,也是为了看看亮司成长的地方,同时也是为了实现自己的诺言。

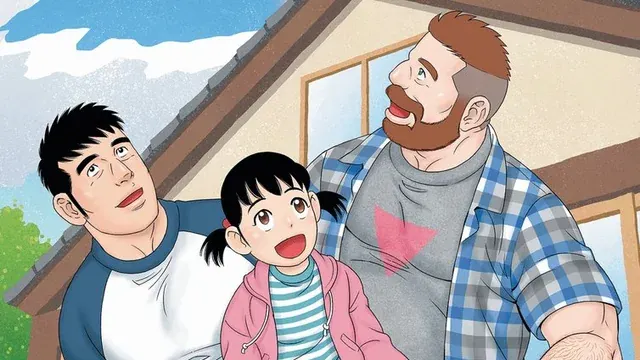

八一一开始很紧张:迈克身材高大,性格温柔体贴。尽管八一很担心(他以前从未见过迈克,除了他的哥哥以外,也从未见过任何同性恋者),但八一的女儿加奈对她的新叔叔充满了好奇。

随着三人相处时间的增加,八一开始了解到,虽然他和亮司在后者出柜后变得疏远了,但亮司一直在谈论他,讲述他们之间的故事。加奈关于迈克的问题和为迈克提出的问题让八一从更纯真的角度看待迈克,并反思自己的偏见--以及如何应对小镇上其他人的偏见。

📺 观看地点: NHK 点播

印象

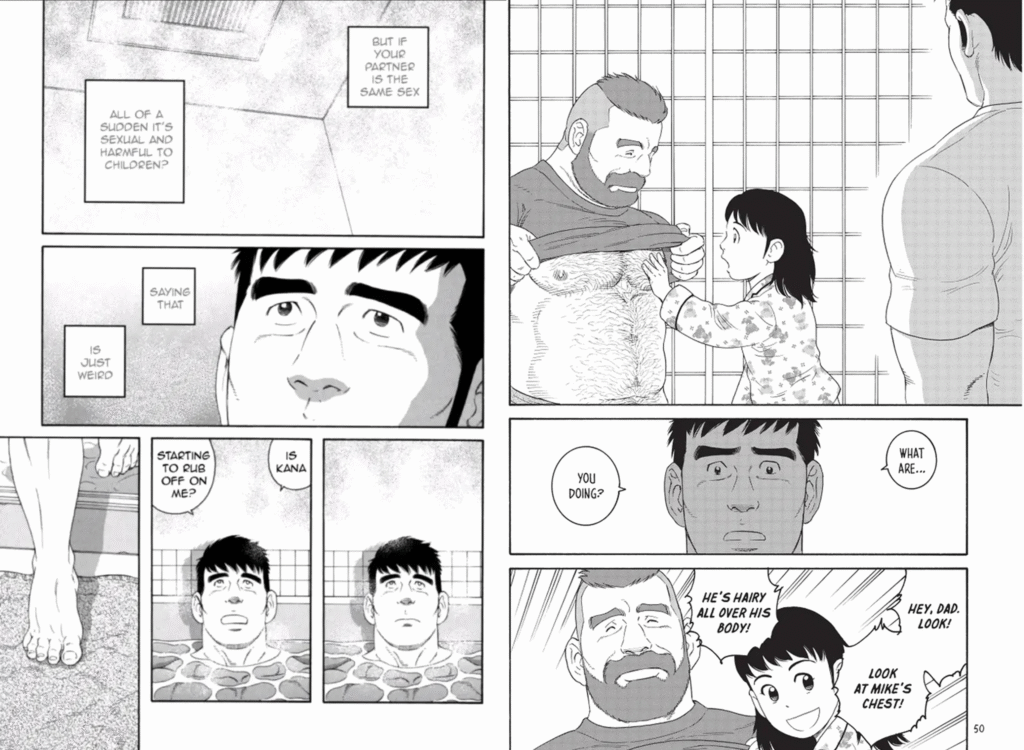

该剧很好地揭示了即使不是主动仇视同性恋的人,在孩提时代学到的根深蒂固的偏见是如何影响个人和家庭的,这些偏见一直持续到成年和整个社会。不过,该剧也强调,这些习得的行为是可以改变的,而且改变永远不会太晚。

八一一开始对与迈克同住感到紧张,因为迈克的长相与他已故的哥哥十分相似,他担心迈克会对他产生感情。这种随意的同性恋恐惧症("我不介意别人是同性恋,只要他们不在我身边做就好!")在全世界已经流行了几十年。虽然现在西方国家对这种现象更加不屑一顾,但在日本,这种现象仍然普遍存在,因为在日本,人们通常认为性行为是一件私事,尤其是在小城镇和社区。

因此,看到八一在迈克这个温柔的巨人面前发生的变化,他慢慢地赢得了迈克的信任(一直快乐兴奋的加奈也帮了不少忙),思想也变得更加开放--从第二集的 "几天前,我还不会和他一起去泡温泉 "到反思 LGBTQ+ 在日本受到的不公平待遇,这一切都让人受益匪浅。他的成长在整个系列中均匀地发展着,同时也带着伤感,因为他知道自己对哥哥也会有这样的感受。

迈克的出现也引起了小镇上其他人的注意:一个小男孩在性问题上挣扎,他向迈克寻求建议;一个偏执的母亲禁止女儿去看望卡娜,她担心迈克会对她产生不好的影响。这些看似平淡无奇的故事情节,却被该剧巧妙而细腻地处理得恰到好处,这在日剧中实属罕见,因为在日剧中,细腻从来都不是一种保证。

演出

佐藤龙太饰演的八一非常出色。佐藤饱含深情地演绎了一个因未能与哥哥和解而愧疚不已的哥哥。佐藤的演技反映了他对迈克以及对自己的日益开放和信任,随着迷你剧的播出,佐藤的演技变得更加松弛和放松。

他不是在一瞬间从一个潜在的同性恋者转变为一个自豪的盟友,而是一步一步地转变,他所表现出的这种情感是真实的、令人信服的,因此很容易让人为他欢呼。

另一边,是由根本麻晴饰演的女儿加奈。她兴奋而热情,表演十分到位,不难理解为何她的父亲开始敞开心扉。儿童演员通常会显得笨拙,但 Nemoto 却演得很好。

Mike 由爱沙尼亚前相扑选手 Baruto Kaito 饰演。他轻松地体现了角色的善良和高大,看起来就像是从漫画中走出来的一样。在最后一集之前,他在很大程度上只是一个侧面人物--一个有影响力的人物,但我们很少有机会从他的角度看问题。这种情况在最后一集中有所改变,我们可以从他的视角看到更多的场景。

海涛的日语说得很好,让人相信他虽然在大学学过日语,但这是他第一次来到这个国家,所以说得有点笨拙(海涛在日本生活了很长时间,在现实生活中无疑说得很流利)。不过,我必须承认,当他说英语时,我还是笑了一下,可惜他的口音与加拿大口音相去甚远!

结论

这是一部优秀的系列剧,演员们精湛的演技巧妙地描绘了一个关于爱情、家庭和 LGBTQ+ 在日本的挣扎的故事,在日本,有时耳语比呐喊更有压迫感。这是一部值得轻松推荐的作品。