Japan is well known for being a safe country, and that includes acceptance of LGBTQ+ people. While not perfect (few places are), there has been an increased level of acceptance and understanding among the people of Japan over the past few decades, and outdated terms like “okama” have gone from being commonplace to being recognized as offensive. But sadly, gay marriage in Japan is still unrecognized.

Japan is the only G7 country that does not accept gay marriage legally, and this has led to a series of legal difficulties for Japanese and international LGBTQ+ people. As you may expect, however, the Japanese queer community hasn’t taken this lying down, and have made many legal challenges to the restrictions against marriage equality, challenging the government’s interpretation of Article 24 of the Japanese Constitution. But what is that?

What Is Article 24 of the Japanese Constitution?

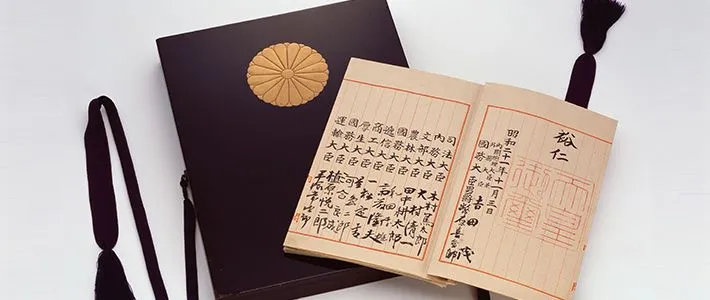

Brought into force with the rest of the Constitution in 1948, Article 24 is designed to outline the opinion of the State of Japan insofar as it pertains to marriage, which is (like all other Articles in the Constitution) the ultimate legal authority on the matter. Below is the entirety of Article 24:

Marriage shall be based only on the mutual consent of both sexes and it shall be maintained through mutual cooperation with the equal rights of husband and wife as a basis.

With regard to choice of spouse, property rights, inheritance, choice of domicile, divorce and other matters pertaining to marriage and the family, laws shall be enacted from the standpoint of individual dignity and the essential equality of the sexes.

Well, that seems somewhat explicit on the surface, doesn’t it? But why was this Article even necessary in post-war Japan?

Interpretations

While the language that is explicit about “husband and wife” and “both sexes,” almost nobody believes that this Article was written with the explicit aim of thwarting marriage equality. After all, this topic, which while important, was not on the political radar of the majority of people in Japan or anywhere else in the aftermath of the Second World War.

Instead, Article 24 is widely considered to be a protection about arranged, forced, and abusive marriages, which were sadly rife in the preceding early Showa, Taisho, and Meiji eras, and before even them. However, the wording means that it can be interpreted to mean that marriage can only be between a man and a woman — and indeed, this is the government’s current position.

History of Court Challenges to Article 24

But that isn’t the only interpretation, nor is it the only Article in the Constitution of Japan. While many opposition parties are in favor of marriage equality, the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) remains opposed. In the absence of legislation, therefore, many people across Japan have taken to the courts to have their rights recognized in the past few years.

In 2019, 13 couples in Japan, including wives Ai Nakajima from Japan and her wife, Tina Baumann of Germany, filed for symbolic damages of ¥1 million each in five different districts across Japan. Here are how the courts responded.

Sapporo

In 2021, the Sapporo District Court rejected the claim for monetary compensation. However, it did rule that by not recognizing the right of people to marry who they want, their constitutional rights had been (and are being) violated.

In 2024, the Sapporo High Court went further, noting that despite the wording of Article 24 being historically being considered to be limited to heterosexual couples, the true purpose is marrying who you want according to free will. Therefore, limiting marriage to only straight couples violates Article 24, and is unconstitutional.

Tokyo

In 2022, the Tokyo District Court also held that preventing LGBTQ+ people from marrying the partner of their choice did not violate Article 24, and was therefore not unconstitutional in that regard. That said, it also ruled that the government’s failure to enact laws to protect the dignity and legal rights of queer couples did violate their rights to individual dignity.

On appeal, the Tokyo High Court did not grant financial recompense, but did rule that the government’s lack of provisions for LGBTQ+ couples to get married violated Article 14, which guarantees equality between all people, and that such discrimination based on sexual oreintation was utterly irrational.

Fukuoka

In 2023, the Fukuoka District Court held that, while the individual freedoms of the plaintiffs were being violated, it nevertheless held that — although acceptance of LGBTQ+ people was at an all-time high — enough people in the public were against marriage equality that it could not yet be considered a constitutional right.

In 2024, however, the Fukuoka High Court ruled on the appeal that in fact, the legal inability for same-gender couples to wed not only violated Article 24, but also Article 13, which guarantees a right to the pursuit of happiness. Although it did not award any money, it concluded that the expansion of partnership systems is not sufficient to create equality.

Nagoya

In 2023, the Nagoya District Court similarly held that Articles 14 and 24 were violated, though it did not award any compensation.

In 2025, the Nagoya High Court upheld this interpretation, not only noting that same-gender couples’ fundamental rights were being violated, but also that the lack of marriage equality inevitably created difficulties for children raised by LGBTQ+ couples, as well as making medical care and decisions in the event of emergency extremely fraught.

Osaka

In 2022, the Osaka District Court broke with its peers in ruling that not only were plaintiffs not entitled to government compensation, but that the ban on marriage equality was entirely constitutional. While it accepted that individual rights were not being respected, it believed that there had not been enough public discussion on the issue for the courts to have a meaningful say.

However, in 2025, the Osaka High Court overturned this decision, ruling that not only was the ban on gay marriage unconstitutional, but that to create some like marriage yet not marriage (such as the UK’s civil partnerships) would create two separate statuses for couples, based on sexuality. This would be an obvious and irrational violation of the right to equality, and therefore the only remedy is to recognize same-gender marriage.

Why Is Gay Marriage Still Illegal in Japan?

So, all these High Courts are in agreement in one sense or another: the lack of marriage equality in Japan is blatantly unconstitutional. So how can it be that it still hasn’t been introduced in Japan?

Well, the first and most significant issue is that (as mentioned) the government of the day, the LDP, remains opposed to accepting marriage equality. Despite popular support among the public, as well as by its coalition partner, Komeito, the right-of-center party is loathe to introduce legislation.

So why does an appeal to the Constitution not work? Well, many in the LDP still accept the interpretation that Article 24 means “one man, one woman,” and believe that the idea that the Constitution itself can be unconstitutional is, on its face, ridiculous.

So, why not amend the Constitution, to simply reword Article 24? Well, while the Japanese Constitution can be amended, it hasn’t actually had any amendments since it came into force nearly 80 years ago.

Additionally, progressives not only believe that the interpretation of Article 24 as applying only to straight couples is wrong (and are supported by court decisions), but they are wary that an amendment to change Article 24 will embolden right-wingers in government and opposition to attempt to amend or erase Article 9, which prevents Japan from going to war.

Local Government and Alternative Efforts

Despite the lack of movement (or, indeed, care) from the national government, local governments have been more pro-active in recognizing relationships between same-gender couples. Although they do not have the power of law, over 90% of local and municipal governments issue and accept Partnership Oath Certificates.

Despite the lack of legal force, many LGBTQ+ couples report happiness that local governments are acting to help grant them the dignity they need, and that many businesses and workplaces accept and honor these certificates. Read more about them here.

Individual efforts

Because Partnership Oath Certificates do not have the force of law behind them, some couples instead take an alternative route, and adopt their adult partner. This may sound highly unusual (and it is somewhat controversial even in the LGBTQ+ community), but adult adoption is not unheard of in Japan, and it bestows a number of legal rights, such as the right to inherit property, take a surname, and make medical decisions for your partner in emergencies. Read more here.

The takeaway from this is the the LGBTQ+ people who put themselves and their relationships in the spotlight by taking their grievances to court and suing the government have proven not just their bravery, but how untenable the State’s position that equal marriage is unconstitutional truly is.

Sadly, it looks like it will still take more public pressure, along with a bolder Prime Minister — or even a new, more considerate government — to enact legislation to finally make the voices of the courts and the people heard, and enshrine in law a right that should have been granted years ago.