Today, there are groups, subcultures, and even subreddits for anything you can think of. But this wasn’t always the case. What were things like in the days before the Internet? In the days before cellphones? Even… in the days before the terms we associate with queer culture existed?

In 1971, a lesbian circle called Wakakusa no Kai was founded in Japan. It is considered one of the earliest lesbian-centered community groups in the country, and was established by Michiko Suzuki.

The name Wakakusa means “young grass,” and “no Kai” is, essentially, “organization.” It symbolizes freshness, new beginnings, and hope. The name reflected a quiet but powerful idea: that women could live differently, honestly, and on their own terms.

In the 1970s, awareness of sexual minorities in Japan was just beginning to grow. While there were already some organizations for gay men (and the decade also saw the launch of the Barazoku magazine), there were very few spaces created specifically for lesbian women. Wakakusa no Kai emerged in that gap.

There was no internet. No social media. Even the word “lesbian” was not widely known in Japan. The term “yuri” itself, now inextricably linked with sapphic love in Japan, came from the aforementioned Barazoku magazine, for gay men. Things were difficult. Connection required courage. Luckily, courage is a resource that the lesbian community — in Japan and across the world — has in spades.

A Place to Talk

The main goal of Wakakusa no Kai was simple but vital: to create a place where lesbian women could gather and talk. The group aimed to reduce isolation, provide a safe space for self-expression, and build networks among women. At a time when coming out was extremely difficult, the group became an emotional lifeline.

They held meetings monthly, often at Suzuki’s home or in small private venues.

In those rooms, women shared their stories about love, fear, family pressure, and the difficulties of being different. For many, it was the first time meeting others who felt the same way.

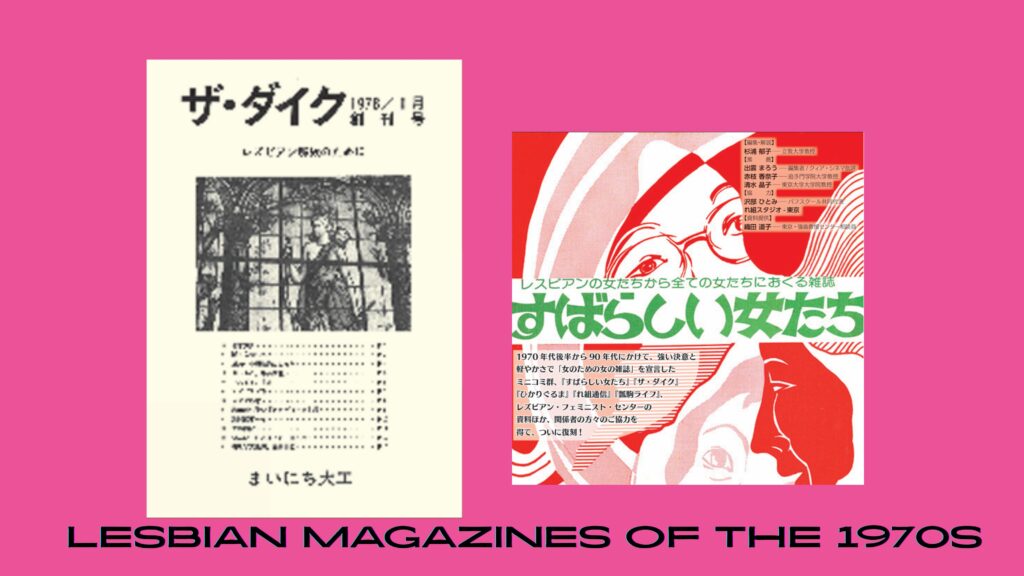

They also published periodicals filled with essays, personal reflections, activity updates, and contact information. Before digital communication, these printed pages carried connections across distance. For someone living alone in a rural area, receiving that newsletter may have meant everything.

When Ideas Grew Stronger

As conversations deepened, some members sought a more political direction. This led to the formation of groups such as Everyday Dyke (whose organ was The Dyke) and Shining Wheel in the late 1970s. These lesbian feminist groups openly connected sexuality and women’s liberation, publishing politically charged mini-magazines and pushing for visibility.

What began as a small circle quietly sharing stories gradually became part of a larger movement.

Then and Now

Today, things are very different, both across the world and in Japan specifically.

We can open social media and instantly find others like us. There are more words, more visibility, more representation. It feels freer… but perhaps the core feeling hasn’t changed.

The women of Wakakusa no Kai were not asking for something extraordinary. They simply wanted to know they were not alone, as well as communicate that feeling to others. They wanted a place where they could speak honestly and be accepted as they were.

Even now, in a world of constant connection, loneliness still exists. The fear of not being understood does not disappear completely. Times change. Technology evolves, but the desire to belong to hear someone say, “You are not alone,” remains the same.

Learning about Wakakusa no Kai reminds us that the connections we have today were built on the quiet courage of women who gathered in living rooms more than fifty years ago. The world may look different now. But deep down, we are still searching for the same thing: a place where we are allowed to exist, just as we are.