As with almost any country in the world, Japan has an at-best chequered history when it comes to accepting and accommodating transgender people. Although today there is, at least in some areas, more acceptance of transgender people (thought some of it can be highly fetishized), and historically men who preferred women’s clothing were also accepted — to a degree.

However, in the aftermath of the Meiji Restoration, and especially into the 20th Century, this tolerance — such as it was — was more or less abandoned. Further, while the new Japanese constitution, which came into force in 1948, guaranteed personal freedoms, there were still a number of societal reasons that trans liberation was not (and still isn’t) realized.

One of the landmark setbacks for the community came in the form of the topic of today’s article: the infamous Blue Boy Trial.

Background

Following the defeat of Japan in the Second World War, which saw Tokyo severely damaged as a consequence of fire bombing, sex work became highly prevalent, especially as occupying forces were in possession of useful foreign currency and good such as cigarettes. The history of Shinjuku Nichome itself was shaped in no small part thanks to these developments.

However, in 1958, while prostitution was outlawed, naturally it still exists if one knows where to find it (something that — I am told — persists to this day). In the run-up to the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, which the government hoped to use as a symbol of Tokyo recovery and emergence as a global city, local authorities and the police made it their mission to “clean up” the city.

As such, many sex workers were arrested — however, the anti-prostitution laws of the time were focused on preventing women from selling sex, and the same did not apply to men who were sex workers, known colloquially as “blue boys.” However, during their investigations, the police discovered that three of the “blue boys” had medically transitioned, and after finding out the identity of the doctor who performed the procedures, arrested them and had them tried.

The Trial

Going to trial in 1965, one of the first issues that the prosecution ran into was that gender reassignment surgery was not, in and of itself, illegal, and the defense argued that the actions of the doctor were valid healthcare procedures for transgender individuals.

As the anti-prostitution laws couldn’t be leveraged against those who may have transitioned but were still legally registered as men, instead the authorities charged the doctor with violating the Eugenic Protection Law.

Clause 28 of the law forbids the unnecessary sterilization of an individual, or any medical procedure that may lead to it (though what was considered “necessary” would be considered abhorrent to modern sensibilities, which is why the law — which had since been renamed — was struck down as unconstitutional in 2024). As such, the prosecution argued that the removal of healthy male reproductive organs and any subsequent vaginoplasty was illegal.

The Verdict

A difficult case to consider, it took four years for the trial to be concluded. In 1969, the Tokyo District Court concluded that, while the individuals were transgender, and as such were entitled to appropriate healthcare, relevant safeguarding examinations and procedures had not been carried out.

It found that, before someone can have their gender reassigned, they must undergo psychological examinations, their family history must be investigated, they must obtain the permission of their spouse (if married) or guardian (if a minor), relevant medical records must be created and stored, and any surgery performed by a competent physician.

Although the court accepted that these particular individuals warranted the medical interventions, because it was beneficial to their health, the doctor in question had not followed the necessary steps, and so was given sentence of two years imprisonment, and a ¥400,000 fine, suspended for three years.

Aftermath

There were two significant outcomes from the case. The first is that, as you may imagine, it was a high profile issue throughout the four years that arguments were conducted until the verdict was delivered. As such, awareness of transgender people (most notably trans women) and gender reassignment procedures was greatly increased among the general public. This could have, hypothetically, helped many transgender people find the assistance they needed.

However, the main effect in the wake of the verdict was that, while gender reassignment surgery was not found to be illegal, the doctor being found guilty and being sentenced to both prison time and a large fine (albeit suspended) led to the misguided perception that it was illegal.

As a result, gender reassignment surgeries, already rare in Japan, were essentially put on hold until 1998, when laws and regulations were more adequately codified (though how “adequate” they are for trans people in Japan today is up for more than a little debate).

This means that for thirty years, Japanese transgender people needed to go abroad for their medical care. Additionally, the three decade gap in local expertise has meant an ongoing knowledge and experience deficit for transgender healthcare that, while improving, persists in Japan to this day.

One final effect of the trial is that the term “blue boy” fell out of use among sex workers, and especially trans women sex workers. It was instead replaced by a term that can be seen across Nichome and even dating apps: “new half.”

Contemporary Views

Today, the trial is regarded as (at best) a regrettable moment in the history of Japanese jurisprudence. While the verdict itself didn’t forbid transgender healthcare, the way the case was made to be salacious and the reporting that surrounding it is considered to have dramatically hindered trans rights in Japan.

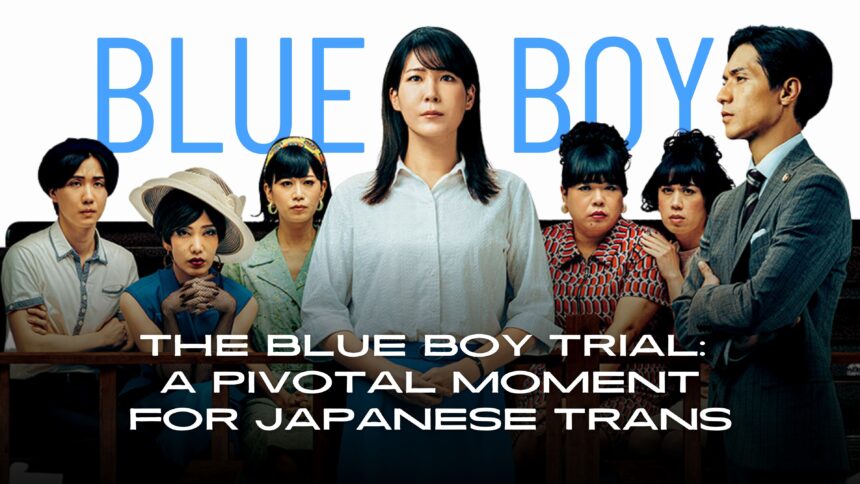

In November 2025, a film based on the case, Blue Boy Trial (ブルーボーイ事件) was released to critical acclaim. Considered both a fascinating look into the Japan of the 1960s, it also leads the viewer to question how much change has really been made in the intervening time when it comes to the perception and acceptance of trans people. It is also directed by and stars transgender talent, adding to the authenticity and emotion of the film.

We hope that this brief recounting of a significant part of Japanese LGBTQ+ history has not been depressing: while things are far from perfect, especially for the transgender community, progress is slowly being made. But we believe it does good to remember not only how far the LGBTQ+ community has come, but also what it cannot return to.