In the age of the blog, the microblog, the vlog, and whatever we want to call TikTok, there are some who may have forgotten — or worse, never experienced — the joy of picking up a magazine that caters exclusively to one’s interests.

This is also true for gay magazines, with Japanese gay magazines (or even Asian gay magazines as a whole) having fallen away as the march of technology rumbles ever on. But what was the history of LGBTQ+ publications in Japan? And have they gone forever? Lucky you, you don’t need a subscription to discover Japan’s queer magazine history.

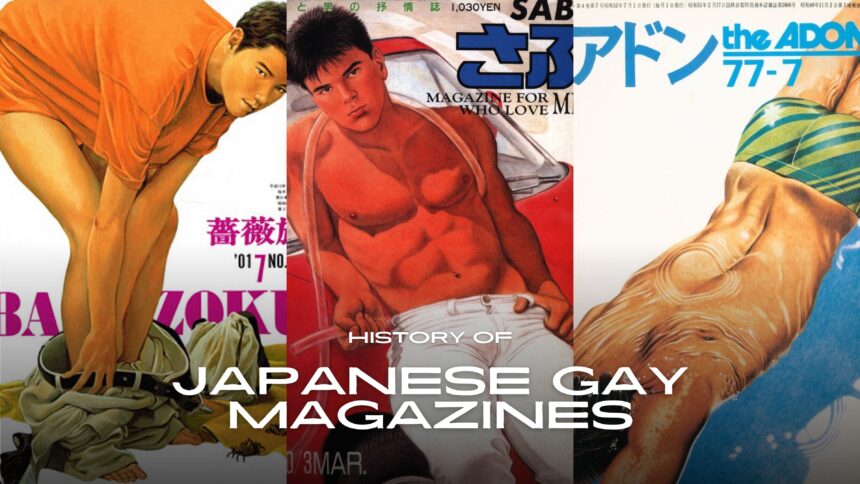

The History of Gay Magazines in Japan

Like much modern LGBTQ+ culture, gay magazines really took off in the aftermath of the Second World War, as queer communities began to gather together in (somewhat) open fashions in major cities, and especially in areas such as Tokyo’s Shinjuku Nichome area.

However, given the somewhat taboo nature of gay magazines, which would (as one may imagine) often feature lewd images and writing that could run afoul of obscenity laws at the time, many (including some early examples such as Adonis) were “members-only” publications. This is to say, in order to subscribe, you had to know someone who had a copy and could give you the address to send your money to, and receive it in the post of collect it from a specialty store.

However, as LGBTQ+ people began to become more visible, and gain a degree of economic power as a group, Japanese gay magazines and publications began to be published in more mainstream settings.

The Rise of Modern Japan Gay Magazines

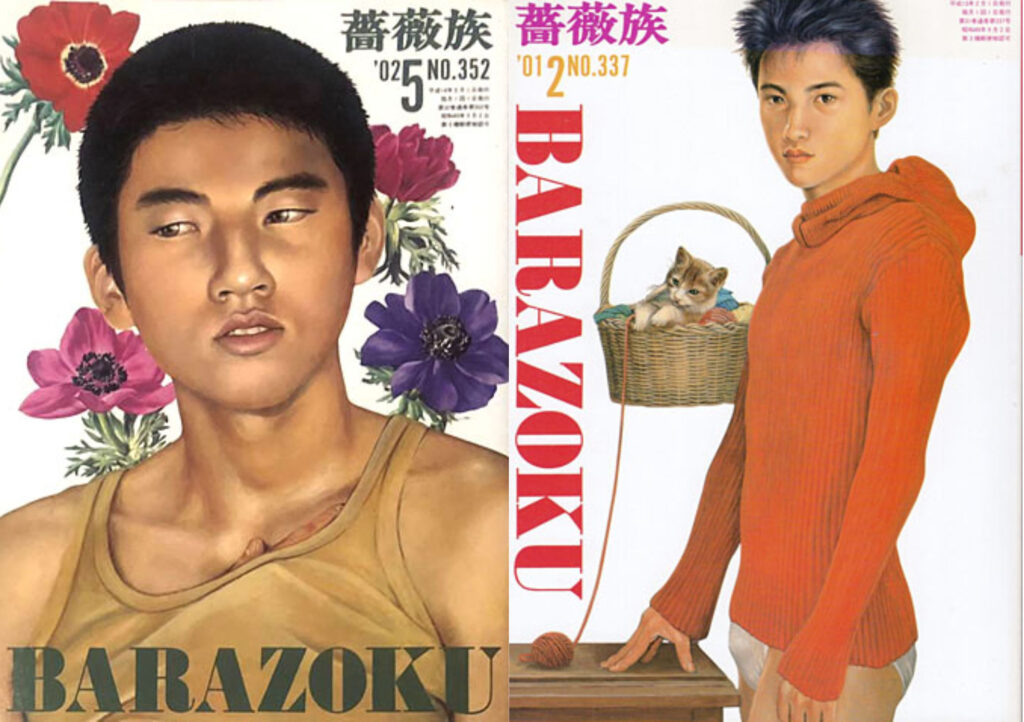

The most prominent example of what we might consider to be a modern Japanese gay magazine is Barazoku. We have previously published a detailed history of the magazine here, allow us to give a brief summary.

Barazoku (or “rose tribe” in English) was the first gay magazine to be stocked in mainstream Japanese bookstores and newsagents, with it’s 10,000 run first issue selling out almost immediately. Featuring photography, manga, fiction, and current affairs stories, as well as classifieds for those who wanted to meet one another, it became the flagship Japanese gay magazine. It is also the origin of the term “yuri” to mean “erotic lesbian content.”

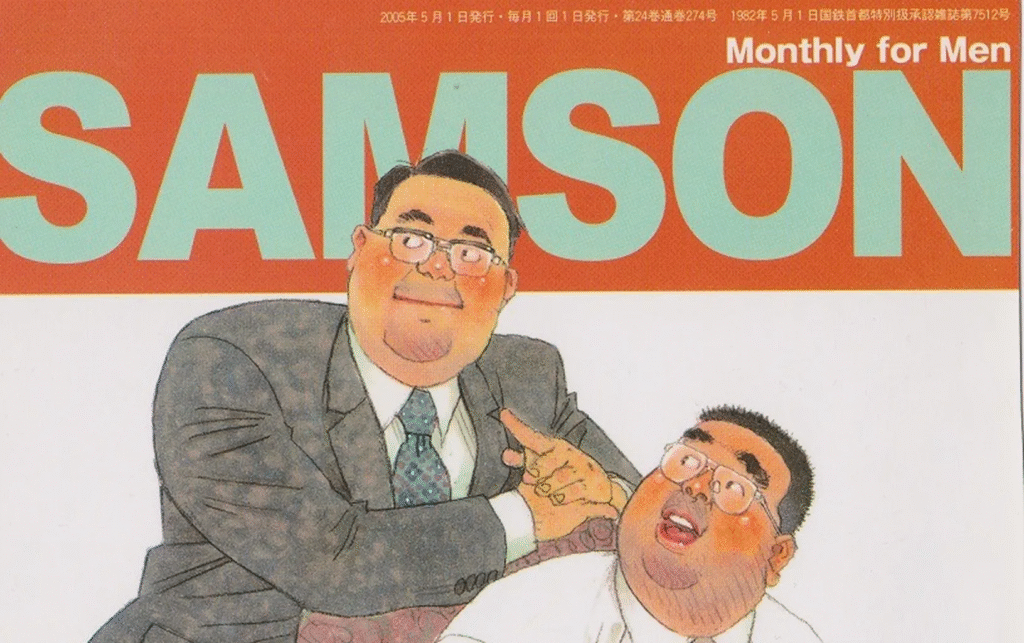

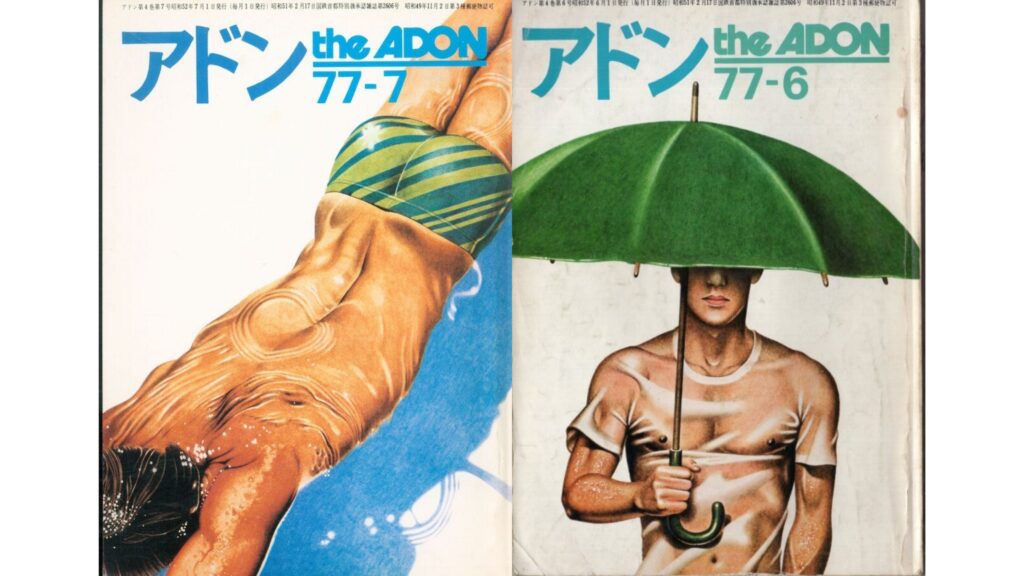

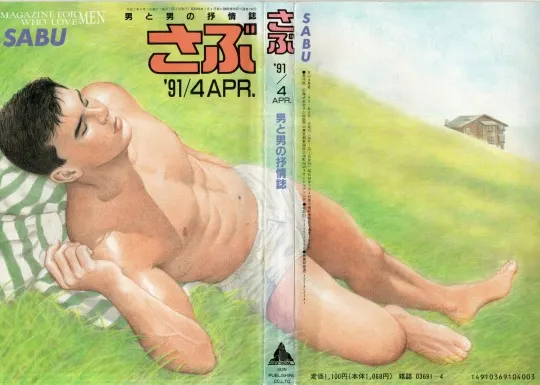

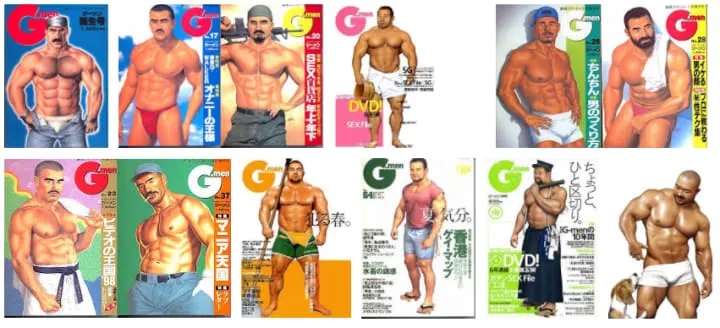

Other magazines emerged in the wake of Barazoku’s success, including Adon, Sabu, G-Men, and Badi. As many bars do today, each of these magazines tended to appeal to those who were either a member of or attracted to a certain type of gay men.

Adon, for example, was known for its love of muscular guys.

Sabu focused on 20th century Japanese masculinity, with crew cuts and fundoshi being popular themes.

G-Men favored the macho man: not just muscular, but broad, and impresive, whether top or bottom.

Badi instead catered to a younger crowd, and the models would be more of the Johnny’s type: more slender and lean.

We might also add to this the rise of doujinshi (同人誌), which are fanwork comics or stories of characters from established series, that were historically sold at fan-run comics conventions, and subsequently through second-hand markets. For our purposes, Boys’ Love (BL) comics that depicted gay romance (often explicitly) between prominent characters became very popular, both among gay men and women.

Asian Gay Magazines and Japan’s Regional Influence

While much of the LGBTQ+ media in Asia developed independently (if it was permitted to develop at all), it was BL doujinshi that had a significant impact across other nations. The expression of queer love in art was instantly intuitive, and helped to promote not just Japanese culture, but queer expression was also transformed and advanced in nations exposed to it. There have even been academic symposia discussing the phenomena.

However, just as BL publications from Japn transformed queer culture in Asia — and even across the world — Japan was undergoing the same societal and technological changes that were spreading across the globe in the early 21st Century.

The Transition from Print to Digital

As the Internet began to become more prominent in daily life — particularly in Japan, where Internet accessible phones were available long before what we would now consider to be smartphones — many subcultures began to flock online. This included many from the LGBTQ+ community. As devoted readers of JGG will be aware, Japan believes that sexuality is a very private affair, and so even declaring one’s sexuality in public can be a relative rarity.

As such, the anonymity of the Internet (especially when it comes to classifieds) meant that people had a much easier and more private way to connect with one another — and this was especially helpful for LGBTQ+ people.

Despite gay magazines being sold openly, and a lack of statute to oppress queer people, social stigma still existed (and, indeed, exists), so it was preferable to use the Internet to explore one’s sexuality and meet one’s tribe, given the safety of anonymity, ease of use, and it being free.

Many magazines made a jump to include websites as a part of their portfolio, but even the great Barazoku, eventually, had to concede that the Internet was, at the time it published its final physical issue in 2008, the future for LGBTQ+ people when it comes to making connections and spreading information.

The same is true of doujinshi. While scans of physical copies proliferated in the early 2000s, today many creators will publish to the Internet directly, to get to their fanbase quickly and directly.

- You can access a digital issue of Badi magazine at this link.

Why Gay Magazines Still Matter Today

Despite this, there is still a thirst for queer content that is physically published around the world, including in Japan. Although commercial magazines have seen themselves superceded, zines — which, for those unfamiliar, are amateur-produced small magazines, often concerned with niche subjects — continue to serve an audience who enjoy original works in a tangible form.

Zines often discuss academic or artistic topics that are neglected by the mainstream, by creators with extensive knowledge of the subjects they are discussing, often for little or no compensation: just for love of the game. As such, articles and artwork about the intersections between LGBTQ+ culture and capitalism, race, climate change, gender, and protest are considered to be authentic, expressive, and well worth the purchase and the read.

The commercial magazine for the LGBTQ+ community in Japan, at least in the form it once possessed, is dormant. However, online resources and zines have moved to fill the gap. I like to think, however, that no good thing is gone forever, and if Barazoku — which folded and came back four times — can revive itself, perhaps it won’t be long before the format does, as well.