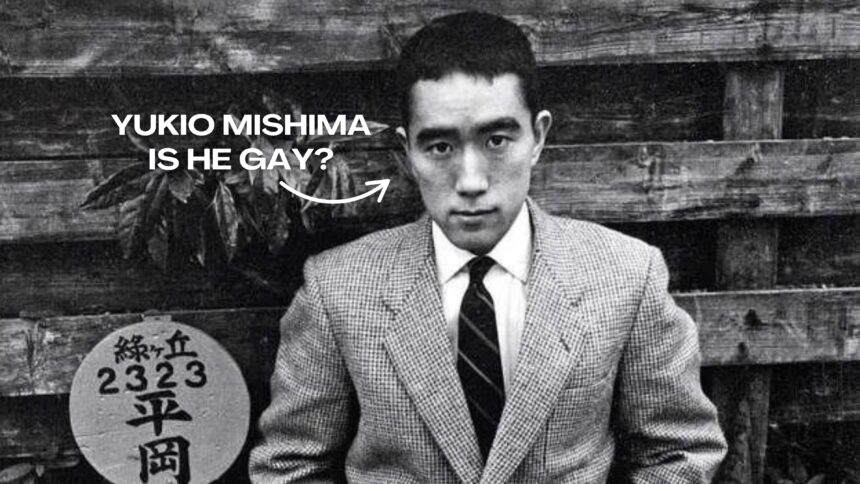

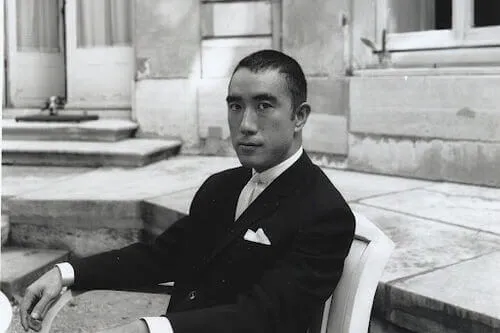

One of the most controversial literary figures in post-war Japan, Yukio Mishima was undoubtedly a literary genius, and was once on the short-list for the Nobel Prize for Literature. Nevertheless, his experiences during the war sent him down a path that eventually ended in his own ridicule… and death.

However, when many people in the west think of Mishima, he is often thought of as “the best gay Japanese author of the 20th Century.” But is that true? Was Yukio Mishima gay? Let’s go through the life and times of a successful author, a thwarted soldier, a failed revolutionary, and one of the most enigmatic figures in Japanese LGBTQ+ history.

Yukio Mishima: A Brief Biography

Born Kimitake Hiraoka in 1925, Mishima was a distant relative of the Shogun Ieyasu Tokugawa. He grew up in his formative years with his grandmother, who separated him from his parents and disallowed him from outdoor pursuits, spending most of his time writing and reading. However, when he returned to his parents, his father tried to excise any “feminine” interests from him — though Mishima still wrote in secret, even after his father tore up his books.

He excelled at school, writing several stories and eventually graduating as class representative. The graduation was overseen by the emperor, who later gave him a silver watch. He was also given the nom-de-plume Yukio Mishima by his teachers after contributing a story to a literary magazine, after the snow that topped Mt. Fuji and the name of the Mishima train station his teachers passed through, a blending of ancient and modern Japan in his pen name.

After being conscripted to the Imperial Japanese Army in 1944, he was classified as a “second class” conscript, and was later dismissed from duty altogether for ill-health. Though his state of mind on this matter is not known for sure (his own accounts conflict with one another), what is known is that he was deeply affected by the “Declaration of Humanity” made by the Emperor. It was this personal and national shock that perhaps motivated his life’s mission. As he said to a friend: “Only by preserving Japanese irrationality will we be able contribute to world culture 100 years from now.”

Following the war, his literary pursuits began to gain more mainstream appeal, despite his pro-Imperialist views being unpopular (and, under occupation, illegal). One of his early successes was The Middle Ages, which told the story of a love affair between the retainer of a feudal lord who committed seppuku and his father, both bereft of the man they loved. It was followed by Confessions of a Mask, which we will delve into in more detail below.

His work saw him become a favorite among foreign readers, and he was considered for the Nobel Prize for Literature for five years running, from 1963 to 1968. He was additionally a model and an actor.

His works, including The of the Golden Pavilion, often drew on recent events, but were rarely openly political: he disliked political figures as a whole, and distrusted those who proclaimed “realism” when it came to dealing with foreign nations. That said, he eventually came to believe that he preferred those with strong will, even if they were innerly without conviction, over charismatic ideologues.

Towards the end of his life, however, his politics became more overt. He wrote Voices of the Fallen Heroes, which excoriated Emperor Hirohito for renouncing his divinity, and wrote the stageplay My Friend Hitler, a play which is interpreted by some as anti-fascist, and others as openly fascist. He began to debate left-wing students, and eventually formed the Tatenokai, or Society of the Shield, made of right-wing students, mostly from Waseda University.

In November 1970, under the pretext of a meeting, he and four allies broke into a military base in Tokyo, where Mishima gave a speech intended to rouse the soldiers below to stage a coup and restore military rule under the Emperor. Instead of a revolution, he was met with incredulous jeers. After retiring inside, he took out a blade and committed seppuku.

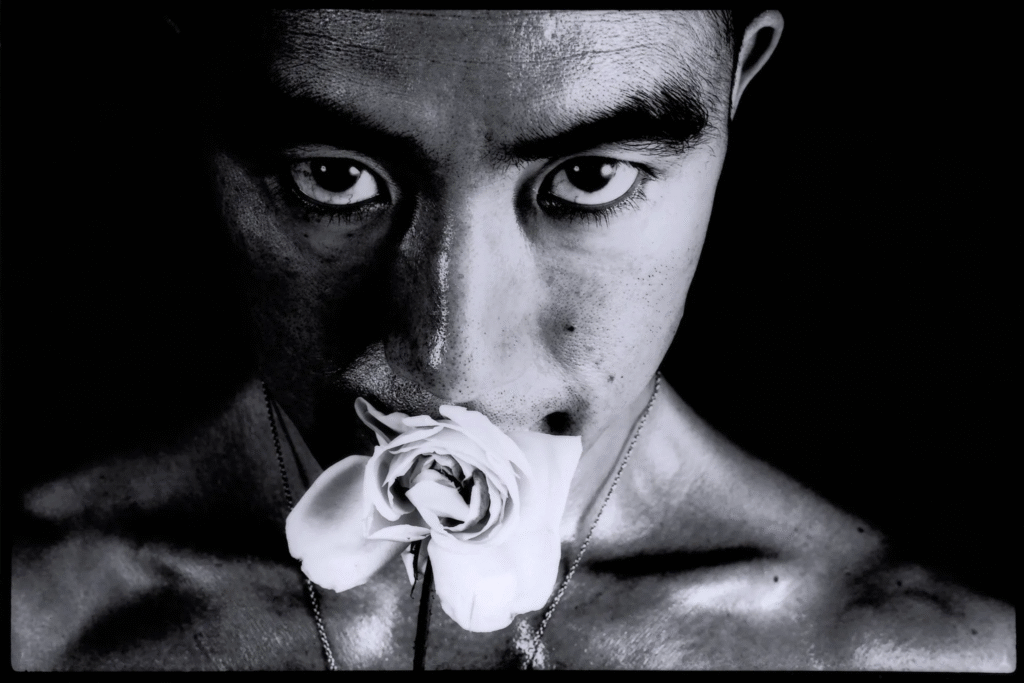

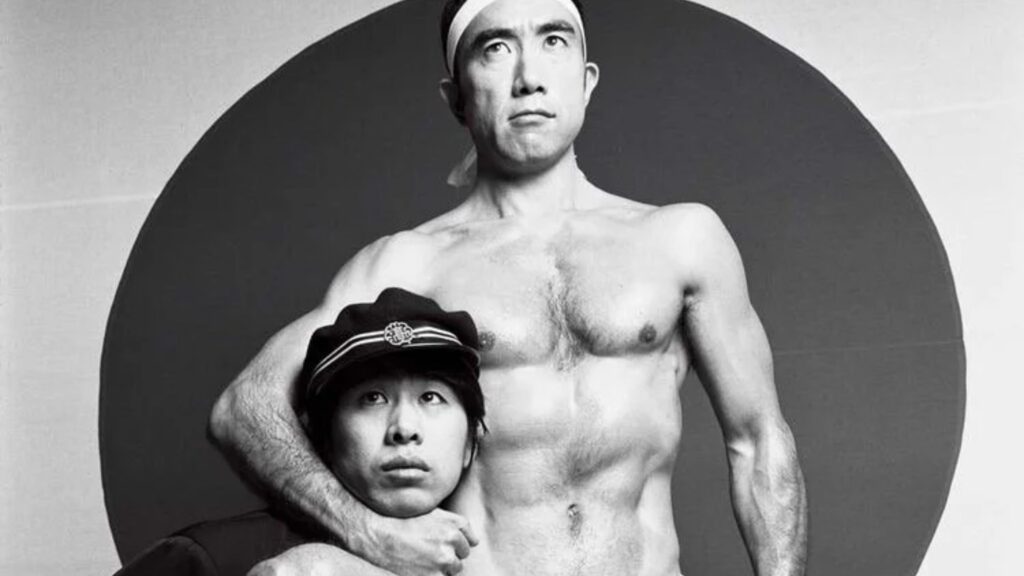

Yukio Mishima’s Obsession with the Male Body

One of the things that bound Mishima and other members of the Tatenokai was a devotion to physical exercise and the perfection of the body. Mishima, despite his artistic prowess and noble background, disdained the intellectual class, who he saw as putting the mind before the body.

It is not lost on historians, however, that his ill-health following his conscription was likely a big motivator into his desire to get physically stronger. He exercised three times a week without fail during his final fifteen years, perhaps due to shame that he was not considered strong enough to fight — or shame that he was happy when he was dismissed, and could not reconcile this happiness with his dulce et decorum est, pro patria mori beliefs.

His obsession with the male body also bled into his works, where he said that “men’s [bodies] must always be tense like the bow which is drawn toward a crisis.” The male form was also the ideal form of patriotism. Unsurprisingly, the Emperor, who was once considered divine (and to Mishima perhaps still was) was once considered to be “the body of Japan.”

Masculinity for Mishima, therefore, was not merely erotic (as will be discussed shortly) but the ideal of what a perfect person, and therefore, a perfect nation could and should be — and this is exemplified in the body of the soldier, the military man than Mishima nearly was, but could not become.

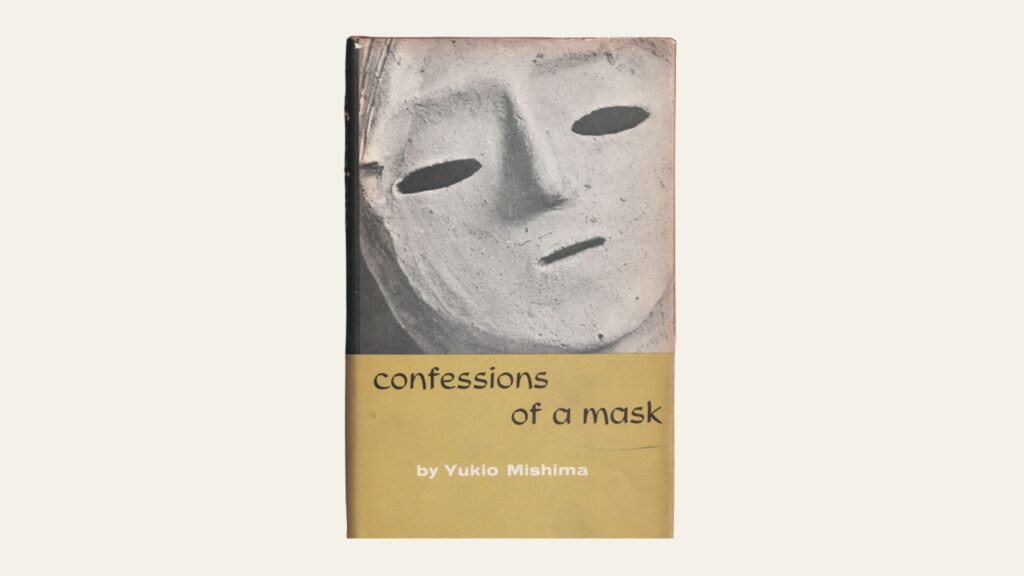

Confessions of a Mask novel and Yukio Mishima’s Gay Themes

Arguably his best-known work, Confessions of a Mask is Mishima’s first “I-novel,” a story that emerged in Japan after the war. To describe the genre in English, “semi-autobiographical” might be an apt translation.

While it might not necessarily be accurate to describe the book as a true story, the protagonist’s name being “Kochan,” a diminutive for of Mishima’s birth name, and is a closeted gay man, who desires men but is unable to act on his desires publicly in Imperial Japan. The story discusses Kochan’s obsession with the male form, and how he needs to build a “mask” to hide his true feelings to the world.

Many critics point to the way his character is initially sexually drawn to a depiction of a powerful European man: only when Kochan discovers that this is actually Joan of Arc, he is disgusted by her, and never feels the same desire for the image. This compounds the ideas of physical masculinity and national purity with sexuality. It could be argued that Mishima’s obsession with militarism, especially later in life, can be explained by a sublimation of sexuality into the macho, and the macho sublimated into ultra-nationalism.

The themes of homoeroticism permeate many of Mishima’s works to some degree or another, often uniting male beauty with national glory. Western readers are sometimes confounded by this: LGBTQ+ creatives abroad are most often (though not exclusively) left-wing in character. So how did Mishima, a man whose work speaks to a longing for me, die in what he saw as service to the Emperor and to his country?

Cultural Context: Homosexuality in Postwar Japan

We must recall that, while with a brief exception from 1872 to 1880, homosexuality in Japan was not criminalized. However, the influence of western morality regarding sexuality permeated much of Japan, especially as it became first an industrial power, and then a world power following its successful defeat of Russia and its First World War Alliance with the victorious European powers.

These feelings were amplified under the pre-war and wartime pressures of Japanese fascism. Under fascism, sex exists only for reproduction, to create workers and soldiers for the state. As such, homosexuality is not just considered strange, but antithetical to the nature of the state and to the conditions of victory.

And these attitudes did not go away quickly, even as the country was rebuilt following its defeat. Therefore, we must recall that it is under these conditions that we must remember that Mishima took a wife, even as he wrote books about how pretending to love a woman would never be enough to bottle up homosexual desire. How he bore two children, while at the same time spending his nights at gay bars in Tokyo.

To say that Mishima would have felt or present differently in a different time is unknowable, and far too bold a claim to make. However, it is sure that just as the war and its aftermath shaped his view on Japan and the nation’s relations to its citizens and to other powers, so it must have shaped his relationship to his sexuality.

Mishima’s Legacy in LGBTQ+ Culture

Mishima is a complicated yet fascinating figure. On the one hand, he was not openly queer — but then, how many people in the 1960s were, in conservative countries where sexuality even today is considered a personal matter?

Mishima was a regular patron of gay bars, and was close friends with Akihiro Miwa, one of Japan’s pioneering drag queens — but he also glorified and wanted a return to the society that would persecute them.

Mishima wrote novels, short stories, plays, and poetry of exquisite beauty — but his heart lay in military might and national supremacy.

And as you may have noted by now, Mishima wrote eloquently and passionately about romantic and sexual relationships between men, and idealized the male form — but there are no confirmed independent accounts of his being in a relationship with men. In 1999, his estate sued an actor who claimed that he had a relationship with Mishima, and the courts blocked the publication of their correspondence, on the basis of copyright infringement.

So, what can we conclude?

Was Yukio Mishima Gay?

Some argue that Mishima was gay, pointing to Confessions of a Mask being an “I-novel”, homosexuality being a recurring subject in his work, and his obsession with fit and strong male bodies.

Others believe he was bisexual, but lacked the words to describe it, in the same way that non-binary people lacked adequate language to describe themselves until recently. They don’t dispute the points above, but note also his marriage, his children, and the lack of any concrete evidence that would “prove” that he was only romantically and sexually interested in men.

Whatever the case, any definitive answer perished in 1970 with Mishima himself, when one of the greatest literary minds of the twentieth Century took his own life after his farcical attempt at a coup d’état in order to restore a rule of law not fit for purpose in the modern day. To his collaborators, his attempt to restore a fascist social order that would likely have persecuted him seemed heroic; to others, bizarre.

While there may not be a definitive answer, Mishima’s life and works certainly embodied the thing he wanted to give most to the world, and which will last for over 100 years: “Japanese irrationality.”