Today, LGBTQ+ magazines, books, and websites are common throughout the world, and Japan is no exception. Indeed, you’re on an LGBTQ+ website right now! But it should never be taken for granted that, for a long time, publications for people who were not heterosexual or cisgender were a rarity, and often published, bought, and sold in a secretive way.

Today, we’d like to take you through the history of Barazoku, the first mainstream gay magazine published in Japan. The story of Barazoku is one of unlikely starts, controversies, lucky breaks, and above all, changing times. Let’s delve into the history of Japan’s Rose Tribe.

Prelude

During the post-war period, the LGBTQ+ community, such as it was, was in a very different space to many of its Western contemporaries. Although not actively and violently repressed, as was the case in the USA and many European nations, homosexuality was often thought of in terms of being a paraphilia: kasutori pulp magazines would portray kink and other fetishes in works that came to be known as the “perverse press.” It was in this context that homosexuality was considered to be one form of kink, rather than a distinct sexuality.

However, this is not to say that there were no efforts to create art and connections. There were magazines, such as Apollo, that were members only, and could only be found in specialist book stores or clubs, rather than in typical commercial locations. As such, it was difficult for gay men who were not already ‘in the know’ to contact one another, or submit pictures or stories that would resonate with one another.

Enter Bungaku Ito, the son of a publisher and a literature graduate whose deep and abiding interest was poetry. After he left university, he joined his father’s business, Daini-Shobo, and watched as the poetry collections that were produced met with acclaim from critics — and apathy from audiences.

After a few years, as the publishing house continued to struggle, Ito (who by now had more or less taken over the running of the business from his father) decided to publish more lurid works, to great financial success. ‘The Night Books’ line of erotica was considered low-class by other publishers and critics, but books such as 1966’s Lonely Sex Life: For the Days of Solitude – which described different methods of self-pleasure – sold out fast. And after the subsequent successes of Homo Techniques: Sex Life between a Man and another Man and Lesbian Techniques: Sex Life between a Woman and another Woman in 1968, Ito realized that there was a vast, untapped queer market calling out for content.

The Launch

To build hype for his upcoming project, in 1970 Ito announced in another of his publications that, in order to foster understanding of, reduce prejudice against, and instill confidence in the gay Japanese community, a commercial gay magazine would be launched the next year. In response, two young men, Ryu Fujita and Hiroshi Mamiya, contacted Ito directly to ask to be editors on the new magazine. Fortunately for Ito, they brought two major strengths to the table: they were both experienced editors, having worked on mainstream magazines in the past; and unlike Ito himself, both were gay men.

This combination was perfect: Fujita and Mamiya were able to focus entirely on the content and output of the magazine, while Ito, who was less experienced in magazine publishing than he was in books and periodicals, fronted the business side and went about convincing major distributors to stock the magazine in their stores. The influence they had over publication was such that Ito himself would later remark, “Fujita was the real editor-in-chief.”

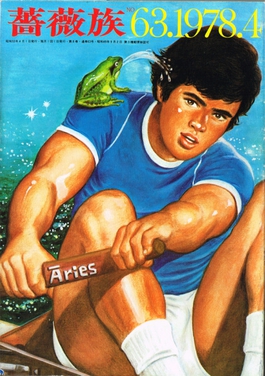

But how was the name decided upon? As you may be aware, “Bara” means “rose” in Japanese, and for a long time was used as a pejorative term against gay men. A suitable English equivalent might be, “pansy.” However, during the 1960s, this term began to be reclaimed by the gay community, most notably with the 1963 publication of Barakei: Ordeal by Roses. It subsequently became associated with erotic gay content, and so was a natural choice to be the magazine’s title. Ito added “zoku,” or “tribe,” as a way to signal to gay readers that they were not alone.

The first issue launched in July 1971, and thanks to Ito’s efforts, it was sold in book stores like Kinokuniya, and its initial run of 10,000 copies quickly sold out, causing a stir in the wider Japanese press — and not for the last time.

Highs and Lows

The second issue of Barazoku saw the magazine get in hot water with Japan’s censors. Japan has strict laws about the depiction of genitalia, but also of pubic hair, and publishers are obliged to blur, mosaic, or otherwise obscure them. Owing to an oversight, one photo depicted a man’s pubic hair in all its bushy glory, and the issue was declared to be obscene. Ito was frightened that Barazoku was over almost as soon as it had begun, but the magazine was let off with a warning.

A few years later, it got into trouble again with a serialized short story, ‘Gay Journey to the West,’ once again falling foul of the censors. This time, things looked serious. Both Ito himself and the author of the work, Mansaku Arashi, were summoned by the authorities and grilled intensely about the story and its overly sensual themes. Eventually, however, while further sales of the story and the 1975 issue that published it were henceforth forbidden, the pair were let off with a slap on the wrist and the investigation was halted — after it was realized that Arashi was related to a former prime minister.

Throughout this period, the magazine continued to grow in readership, and even opened popular cafes for regular readers of the magazine to gather and discuss articles and interests. It even had an impact on lesbian culture in Japan, with a column for women readers to air their thoughts called “yurizoku,” following the long-time association with the beauty of the lily, or yuri, with the beauty of women. The term has since become associated with erotic WlW material.

During the 1980s boom, Barazoku expanded into selling erotic videos and manga, as well as releasing explicit gay movies into the cinemas, which due to the magazine’s reputation came to be called “bara-eiga” as a genre. It also expanded the size and scope of its magazine, with more personals and photographs. During this time, it also published the first interview ever with a Japanese AIDS patient.

Decline and Fall

Despite these successes, as the 1980s bubble burst, and businesses across the country faced financial hardships, Barazoku was no exception. A nearly perpetual phoenix, it closed and reopened three times, before finally coming to an end in 2022, with back-issues being made available online for fans and anyone who wanted to peer into the past of LGBTQ+ history.

But Ito didn’t feel bad about the eventual and, as he saw it, inevitable conclusion of the magazine’s story. The new millennium saw greater representation of gay people in popular media, and the advent of the internet, especially on mobile phones, meant that communication between gay people was now much easier and faster, making the monthly personals of Barazoku obsolete.

With Barazoku as a business eventually evolving beyond its radical roots and into a more overtly capitalist venture seeking the pink yen, there are discussions to this day as to how relevant a gay magazine run by a straight publisher could have been in the 21st Century, even if it had survived. But its importance as the first commercially published gay magazine in Japan — indeed, in akll of Asia — and the spaces and opportunities it opened for gay people during its more than three decade run is undisputable. The magazine may be gone, but the tribe still thrives.